|

|

|

|

|

| From

Embryo to Ethics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When

the neural tube closes early in the development of the

embryo, some of the cells on its dorsal side separate

themselves from this tube to form the neural

crest. These cells then migrate throughout the embryo.

Those in the rostral portion of the crest form the cranial

nerve ganglia, the parasympathetic ganglia, the Schwann

cells, etc. The cells in the caudal portion give rise to

the dorsal root ganglia, sympathetic ganglia, intestinal

ganglia, etc.

Though the migration route of these cells is determined by

their position along the neural crest, the specific final position

of the neurons is not determined at the start of migration

but is instead strongly influenced by the environment encountered

in the course of it.

Experiments with neural crest cells isolated and grown in

vitro have also shown that the choice of the neurotransmitter that

a neuron will synthesize is not completely preprogrammed either.

On the contrary, the environment in which the neuron develops

will affect the expression of its capabilities

for synthesizing neurotransmitters. Thus, some extrinsic

chemical factors are needed to activate or deactivate the genes

that control certain neurotransmitters. |

Researchers have developed

special strains of mice with certain mutations that help

provide a better understanding of neuron migration. One of

the best known examples of these strains is the weaver mouse, which

has a tentative, trembling posture. In this mutant mouse,

the granular cells of the cerebellum die before they can

migrate in the inner granular layer and form their parallel

fibres. Contrary to what was initially believed, this mutation

does not seem to affect the radial glia that guide the migration

of these granular cells. Instead, it seems to affect a component

of a potassium channel in the granular cells themselves.

The result is catastrophic for all of the circuits of the

cerebellum and leads to the motor problems observed in this

mutant mouse.

|

The time at which a

neuron is generated helps to determine its final position

in the brain and therefore influences all of its future connections.

The first neurons generated within a given proliferative

unit are located in the deepest layers of the cortex. Because

these deeper layers will thus already be occupied, the neurons

generated later will migrate farther, to constitute layers

closer and closer to the surface of the cortex. It therefore

follows that neurons that occupy the same layer are approximately

the same age. |

The first neurons form

at the end of the 4th week of gestation. Starting on the

33rd day, differentiated development of the spinal cord and

the brain can be observed. Between the 2nd and the 5th month,

the formation of neurons reaches its peak; it is completed

a few months after the baby is born.

The rudimentary structures of the cortex begin

to appear after 6 weeks. Around the 10th week, the neurons

begin to form

connections. This is the start of the communication

network that will enable the individual to generate appropriate

behaviours. |

|

|

| HOW STEM CELLS FORM

NEURONS |

|

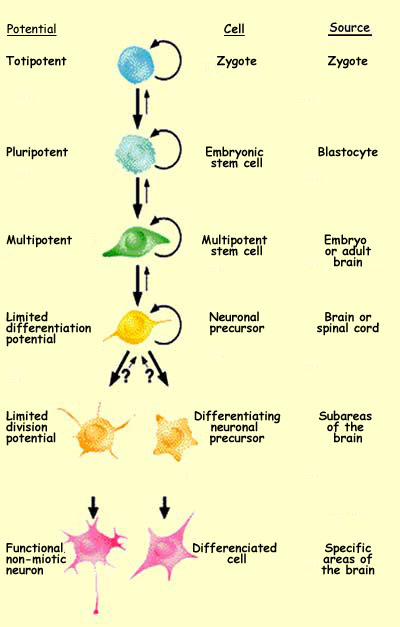

Starting with its very first mitosis, the zygote begins

a long process of cell

differentiation. As it proceeds through the various phases

of its development, the potentialities of its various cells gradually

become more limited.

The totipotent

zygote, which is capable of producing the entire organism,

will first divide into pluripotent cells that do not have this

ability but can nevertheless produce all the tissues of the

organism. Next will come multipotent cells, which can produce

various cells within a particular tissue. And last will come

specialized cells.

Since all of the cells in a person’s body contain the

same genetic inheritance from that person’s parents,

the factors that determine the location, morphology, and function

of a future neuron are necessarily linked not only to the presence

of specific genes but also to their expression and, ultimately,

to their products: special proteins called transcription factors (follow

Advanced Tool Module link to the left).

In the layers of the telencephalic

vesicles that will form the cortex, a veritable cellular

choreography takes place during the proliferation phase that

produces the neurons and glial

cells.

|

|

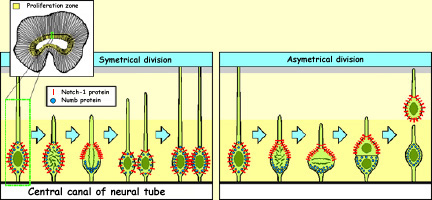

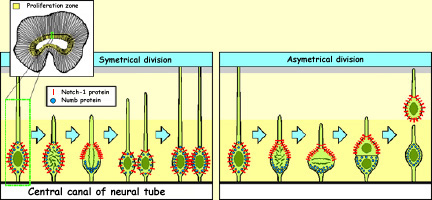

The cell

proliferation phase begins when a cell in the ventricular

zone of the neural tube sends an extension through its marginal

zone to its outer surface, at the pia mater. The nucleus of the

cell itself then migrates into the marginal zone along this extension

while replicating its DNA. Next the nucleus, which now contains

two copies of its genetic material, heads back into the ventricular

zone. The cell then retracts its extension and divides in two.

The fate of the resulting two daughter cells depends on many factors.

The first of these is the orientation of the plane of cleavage

during cell division. If the cleavage takes place in the vertical

plane, the two daughter cells will remain in the ventricular zone

and divide again. But if the cleavage takes place in the horizontal

plane, then the daughter cell that is farther from the ventricular

zone will no longer divide and will begin migrating to its ultimate

location. The other daughter cell will remain in the ventricular

zone and continue dividing.

Hence, during the early stages of development, vertical cleavage

predominates, to increase the population of neuronal precursors.

Later, the pattern reverses, and horizontal cleavage becomes the

rule. In this latter case, the uneven distribution of some transcription

factors in the parent cell contributes to this differentiation

(see the explanation below the following diagram, and follow the

link below for a discussion of more recent results that call this

hypothesis into question).

| |

If certain transcription factors

are not uniformly distributed in the cell before it divides,

then when division takes place, the cleavage plane may be such

that one of the daughter cells receives all of a given transcription

factor while the other receives none. This difference will

affect their futures.

One such case involves two kinds

of proteins, Notch1 and Numb, which migrate to different

poles of the neurons in the ventricular zone. When these

neurons divide vertically, both proteins are distributed

symmetrically between the two daughter cells. But if the

neurons divide horizontally, then the Notch1 proteins end

up in the daughter cell that begins migrating to its final

position, while the Numb proteins remain in the daughter

cell that stays in place and divides again. Notch1 therefore

seems to be the trigger for the genetic program that causes

cells to cease dividing and to migrate toward their final

locations. |

|

Most of the neuroblasts migrate over distances that are appreciable

when measured on the scale of the embryo. These distances range

from just a few millimetres (for cells migrating to the pia mater

in the primate cortex) to far greater distances (for cells migrating

from the neural

crest to the peripheral

nervous system).

Depending on their areas of origin and their destination, neuroblasts

use different methods to guide themselves during their migration.

The cells that come from the neural crests and migrate to the peripheral

nervous system, as well as those neurons that will form clusters

called nuclei in the brain, orient themselves chiefly by means

of cell

adhesion molecules. These molecules are located either in the

extracellular matrix or on the surface of other cells that these

migrating nerve cells encounter along their way. In addition, each

migration pathway thus determined provides opportunities for the

migrating neuroblasts to interact with various cell environments

that emit inductive signals which alter the neuroblasts and contribute

to their differentiation.

|

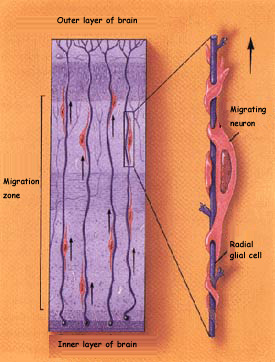

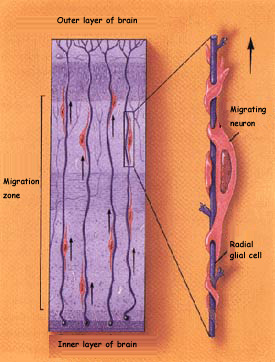

The other major method of migration

is observed in those brain structures where the cells stratify,

such as the cerebral

cortex, hippocampus,

and cerebellum.

In these structures, the neurons reach their final destination

by climbing along glial cells of a particular type, known

as radial glial cells. The migrating neurons use these glial

cells as highways and are pulled along them by the affinities

between the neurons’ own adhesion molecules and those

of the glial cells.

However, one-third of the neuroblasts

do not take this radial migration route, which can lead to

a certain horizontal dispersion of the cortical neurons derived

from the same precursor. |

The first neuroblasts that migrate from the venrtricular zone

are destined to form a layer called the cortical subplate,

which disappears in a later phase of development. The neuroblasts

that are destined to form the six

layers of the cerebral cortex then cross through this subplate

and form a new layer called the cortical plate.

The first cells to reach the cortical plate form layer VI in the

cortex; next come the cells that form layer V, then layer IV, and

so on, from the inside out.

As a result, the neurons that are born first are located in the

deepest layers of the cortex, whereas the younger ones are located

in the layers closer to the cortical surface. This migration guided

by the radial glia also provides an embryological explanation of

the columnar structure of the cortex. Each group of stem cells

in the ventricular zone naturally gives rise to a column of closely

interrelated neurons in the cortex.

Eventually, once the cortical neurons have reached their destinations,

the radial glial cells will retract their extensions. By the end

of the process of corticogenesis, the ventricular zone has become

nothing more than a single layer of ependymal cells that marks

the boundary of the cerebral ventricles.

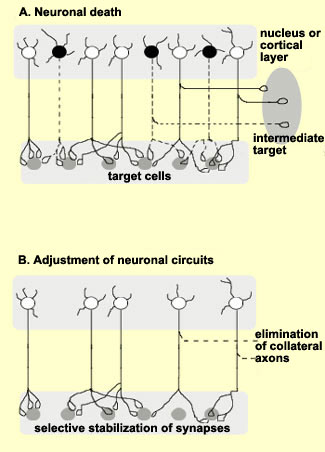

Not all

neurons complete their migration successfully. In fact, the

experts believe that only one-third do so. The other neurons

either die and disappear during the two to three weeks that

the migration lasts, or they never differentiate,or they

survive and differentiate, but not in the right location.

This last group of cells may be the cause of various disorders,

ranging from learning disorders and dyslexia to epilepsy

and schizophrenia.

|

Each cell

individually is not required to undertake the entire journey

that leads from the activation of specific genes to the fulfilment

of this cell’s function in the organism. Many decisions

are made very early in development and throughout the differentiation

process. Because differentiation is a process that does not

reverse, the cells begin by activating genes responsible

for general functions of a given type of organ, but save

until the end the precise adjustments needed to place the

cell in its final position in the organ.

|

|

|