|

|

| Funding for this site is provided by readers like you. | |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

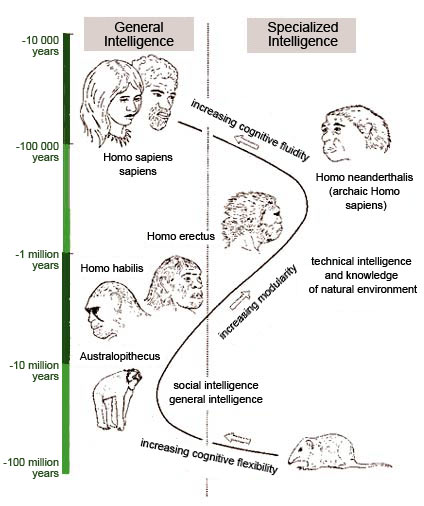

When did consciousness appear? This question can be applied to the evolution of species just as much as to the life of an individual. In the first case, the question amounts to, “Which animals species are endowed with some form of consciousness?” In the second, it becomes, “When, in the course of its development, does a human fetus, baby, or child become conscious?” In this section we will discuss the first of these questions: the phylogenetic origins of consciousness. This question is closely related to the possible functions of conscious phenomena, because if consciousness does have a function, if it is good for something, then natural selection (follow the Tool Module link) might act upon this function. To the extent that this function gives conscious individuals a reproductive advantage, they would pass on to their descendants the genes involved in conscious processes. To begin with, we can be fairly certain that consciousness is adaptive, at least when it is understood in the minimal sense of wakefulness. Without being consciously awake, no individual can feed itself, mate, protect its young, or take any other actions necessary for survival. Next, some authors, such as Susan Greenfield, argue that the emergence of consciousness was a gradual process, keeping pace with the growth of the brain over the course of evolution and hence with the size and growing number of neuronal assemblies. But other authors, such as Nicholas Humphrey, instead believe that the emergence of consciousness occurred rapidly and was more of an “all or nothing” phenomenon. Humphrey thinks that consciousness appeared later in evolution, when our hominid ancestors first developed numerous, diverse social skills (follow the History Module link), such as imitation, deception, language, and the ability to construct a theory of mind for other individuals. Humphrey thus belongs to the school of thinkers who believe that consciousness may have constituted an evolutionary advantage, but not all theorists agree with him on this matter . For Humphrey, consciousness is an emergent property that evolved for its social function. Like the species of great apes that are alive today, we humans have always lived in complex social groups in which knowing other individuals’ intentions can be extremely helpful for determining who ranks above us in the social hierarchy, whom we can trust, with whom we can form alliances, and so on. In other words, according to Humphrey, those of our ancestors who were able to understand, predict, and manipulate other individuals’ behaviour had a definite adaptive advantage. They thereby became what Humphrey calls “natural psychologists”. Some might counter that humans could very well have acquired these skills simply by observing other peoples’ behaviour and its consequences from the outside, somewhat like the behaviourists. But Humphrey thinks there was a better way to do it. He hypothesizes that individuals acquired the ability to look at themselves, to put themselves in someone else’s place and try to see how that made them feel inside. For example, in today’s terms, such individuals might say to themselves, “I can experience jealousy so as better to understand what someone else feels when they are jealous, which lets me better predict their behaviour.”And Humphrey’s hypothesis is that evolution favoured those individuals who had this ability over those who did not. Humphrey compares this ability to a new sensory organ that would be oriented not toward the outside world but toward the individual’s inner world, the activity of the individual’s own brain. Of course, this “inner eye” would not see the brain’s functioning at the neuronal level, but would instead see a more “user-friendly” psychological version of this activity: what we call subjective conscious states. According to Humphrey’s theory, consciousness thus appears as a feedback loop whose function is to provide human beings with a sophisticated tool that lets them become good “natural psychologists”. But we might ask, doesn’t assigning this role to an “inner eye” make Humphrey’s a dualist theory, or give rise to an infinite regression? No, responds Humphrey, who reaffirms his materialist position by reaffirming that the brain is indeed a machine made of neurons and molecules. And his theory does not give rise to an infinite regression either, he argues, because for him, consciousness is not a characteristic of the brain as a whole, but only this loop in which the output, through the mechanism of feedback, becomes the input. There are several other theories on the evolutionary origins of consciousness that have the same overall thrust as Humphrey’s original proposal. For example, British archaeologist Steven Mithen also posits a function for consciousness in social mammals, but he takes Humphrey’s reasoning a step further. According to Mithen, Humphrey’s theory accounts only for humans’ consciousness of their social relations, whereas in fact humans can be conscious of many other things as well. In Mithen’s view, it was this broadening of the field of consciousness that was the critical factor in the creation of the conscious abilities that humans have today. According to Mithen, the first hominids developed several specialized mental modules, largely independent of one another. In Homo habilis, and even in the Neanderthals, social intelligence might still have been isolated from the intelligence needed to manufacture tools or to interact with the natural environment. What we call consciousness was at that time in a sense the prisoner of this social intelligence and incapable of being extended by the rest of these specialized modules. Mithen thinks that these other modules therefore had only a fragile, fleeting form of consciousness, insufficient to let individuals engage in introspection about their methods of manufacturing tools or hunting, for example. It was only as the “fluidity” among these various modules gradually increased that they may have become able to share their content and give rise to the human mind as we know it today. Mithen believes that this process may have coincided with the cultural explosion that the human species experienced some 30 000 to 60 000 years ago. Mithen also embraces the theory that human language evolved as a substitute for mutual grooming in apes, as the size of hominid groups increased. The case that language may have had this kind of social origin is buttressed by the tendency of today’s humans to use language mainly to find out what one person said out about another, or what someone’s social status is, or whom they are sleeping with—in short, to gossip.

Another important phenomenon in social species is deception: the ability to mislead other members of the group so as to more readily secure resources for oneself. Evolutionary theorist Robert Trivers sees this phenomenon as central to our understanding of conscious phenomena. He argues that in those species where a selection for deception occurred, a parallel selection for self-deception took place as well. Trivers points out that we all try to present ourselves so as to appear better than we actually are. But in addition, Trivers believes that because people who believe their own lies make the best liars, there may have been significant selective evolutionary pressure in favour of self-deception. Our ability to fool ourselves would thus have evolved in parallel with our ability to fool other people. Indeed, when we believe our own lies, there is less risk that we will let someone else perceive any emotions or other signs that might contradict them. Because we have unconsciously suppressed part of reality and therefore have a biased vision of it ourselves, we find it easier to mislead other people, and this would constitute a selective advantage for social individuals such as we. The whole scenario seems to suggest that our brains have developed a propensity to keep excessively compromising information beyond the reach of the conscious processes that govern our interactions with other individuals. But at the same time, our brains seem to have kept this information active in unconscious processes so that we do not isolate ourselves too much from reality. For Trivers, deception of others and self-deception are thus intimately linked and form a dynamic that is decisive for the origin of our conscious and unconscious processes. While many theorists such as Humphrey, Mithen, and Trivers thus regard consciousness as a function for adapting to the social aspect of the human way of life, other theorists either express skepticism about this adaptationist tendency in evolutionary approaches or flatly reject the idea that consciousness might have any function that might have made it the target of selective processes.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Most people naturally accept that they are responsible for their own actions. Indeed, when someone says that their behaviours are controlled by a force outside themselves, that is often the sign of some psychological disorder.

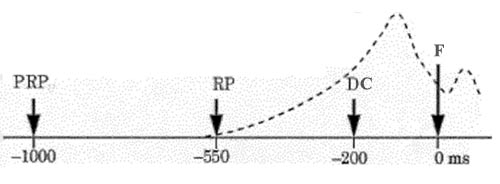

However, many scientists, such as Daniel Wegner and Henri Atlan, and many philosophers, such as Michel Onfray, believe that our conscious will may play a smaller role in our decision-making than we think. In fact, many of these thinkers believe that it might well be nothing but an illusion. They thus call into question our entire societal logic that is based on free will. These thinkers believe that every individual is determined by countless genetic and cultural factors with interactions that are so complex and that we are still so far from understanding that we have an exaggerated impression of our own freedom of action. But if we therefore attempt to incorporate free will into a materialist conception of the brain and the physical laws that govern the universe, we soon see that that is no easy undertaking either, as witness the past centuries of debate that have surrounded this question. In recent decades, however, the neurosciences have helped to advance this debate by exploring the mechanisms of consciousness within the brain. Perhaps the most hotly debated neuroscientific experiments on conscious intention and voluntary action were conducted by neurobiologist Benjamin Libet in 1983. In these experiments, the subjects were simply asked to flex their wrists at a moment of their choosing. The only other thing they had to do was keep an eye on a circular screen on which a spot of light was revolving, and remember the “clock position” of the spot at the moment they decided to flex their wrists. During each experimental trial, the subject performed 40 of these wrist flexions while Libet and his colleagues measured three things. The first was the start of the wrist movement, measured with electrodes attached to the wrist and connected to an electromyograph (EMG). The second was the fluctuation in brain activity associated with the decision to move the wrist; this fluctuation too was measured relatively easily, by means of electrodes attached to the subject’s scalp and connected to an electroencephalograph (EEG). The third thing measured was the moment that the subject consciously decided to make the wrist movement, and this measurement posed the greatest challenge. If the experimenters had asked the subjects to report this moment verbally, that would have created interference with the EEG recording of their motor activity. To get around this problem, Libet used an indirect method that he had tested in various earlier experiments. In those experiments, the subjects had to estimate the start of other events by remembering the position of a spot of light revolving around a circular screen. From these controlled experiments, Libet had concluded that this device was reliable enough to enable his subjects to note the precise moment when they they decided to make each wrist movement. The results of Libet’s three sets of measurements clearly showed a characteristic brain activity called a “readiness potential” (RP) that occurred approximately 350 milliseconds (ms) before the time that the subject reported as when he made the conscious decision (CD) to flex his wrist. Then, 200 ms after this decision, the wrist actually flexed (F). The conscious decision therefore occurred well after the brain had begun to alter its activity in preparation for the movement. And in some cases where the subject reported having prepared the movement internally before executing it (PRP), this lag was even greater: up to 800 ms before the subject consciously decided to make this movement.  After Libet (1985) How these results should be interpreted became the subject of a debate that continues to this day. If brain activity in preparation or readiness for a body movement was observed prior to the conscious decision to make that movement, didn’t that sound the death knell for free will? Didn’t it show that our consciousness of our own intention to act is really nothing more than an epiphenomenon, an effect of our brain’s activity rather than its cause? These results were unsurprising to many scientists who already rejected out of hand any form of substance dualism in which free will was endowed with a sort of immaterial autonomy. Indeed, these scientists would have been disturbed by the opposite finding—a consciousness that did not correspond to any brain activity but was capable of inducing an activation of the brain’s neurons, as if by magic. Such scientists were therefore quite comfortable with the idea that conscious will might be a kind of illusion. But for other scientists, such as Libet himself, consciousness can retain a causal role in our voluntary actions. However, this role is simply that it can exert a control over the movement before it is executed, in the last 150 to 200 ms before the subject’s wrist moves. The decision that was initially made by an unconscious process could then be either approved or overridden by the subject’s conscious will. According to Libet, the extent of our free will would thus be limited to inhibiting the action, to exercising a sort of “veto power” over its execution. Thus, confronted with the myriad intentions that arise at random from the circuits of the brain, our free will would have the power to reject all those intentions that were inappropriate. Personal responsibility would thus be preserved, because we would still be able to suppress the idea of any socially unacceptable action before we externalized it. Many criticisms, both philosophical and methodological, have been levelled at Libet’s experiment and at the conclusions that he draws from it. First of all, some critics have pointed out the difficulty of experimentally testing Libet’s hypothesis of a conscious “veto” function. How, they ask, could consciousness approve or reject a course of action without having assessed its potential consequences first? And if this veto is a conscious act, then it too should require that 350-ms delay to take effect—a bit too long for the 200-ms interval available. Other critics have directly attacked the dualist assumptions that they saw in Libet’s interpretation, which they said granted an almost magical power to this conscious control. The main methodological criticisms have involved the use of the revolving spot of light on the circular screen to measure the moment when the conscious decision was made. Some critics have argued that this method failed to account for the time delay that the subjects needed to shift their attention from the spot of light to the conscious decision to move their wrists. Many other critics have also questioned the choice of a wrist flexion as the behaviour to be observed, on the grounds that it was too simple and repetitive to allow any general conclusions regarding free will or moral responsibility to be drawn from it. These last criticisms have themselves been criticized in turn by Haggard and his colleagues, who reproduced Libet’s experiment and showed that two types of brain waves needed to be distinguished during the interval when the action was being prepared: a first, unconscious wave that corresponds to the triggering of the action (“go ahead, move it”) and a second, conscious wave associated with the type of movement chosen (“move it this way”). But probably the most radical criticism has come from Daniel Dennett, for whom the very idea of wanting to assign a precise moment to a conscious decision is erroneous. Dennett’s conception of consciousness leaves no more room for a place where the subjective awareness of a stimulus such as a spot of light on a dial could coincide with the awareness of initiating an action than it does for a “self” that might observe this coincidence. According to Dennett, all that exists are brain mechanisms capable of estimating time and responding by words or behaviours to these time estimates. Hence there is no possibility that a “self” might have privileged access to the content of this time estimate and the conscious ability to decide on an action. But this does not mean that Dennett necessarily rejects any notion of free will out of hand. He does of course reject any form of free will that would emanate from an immaterial power, but he also believes that our feeling of free will is real. According to Dennett, this feeling might be the conscious expression of a faculty that has evolved to let us weigh the pros and cons of the situations that we encounter in which we are presented with multiple options. The fact remains, however, that this faculty gives us a strong impression that it is our conscious decisions that cause our actions. How can this persistent impression be explained? Daniel Wegner’s experiments showing that a feeling of free will can be induced or, on the contrary, undermined , shed much light on this subject.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|