|

|

The maximum jet lag

that you can experience is 12 hours. If the difference between

your flight’s departure point and its destination exceeds

12 time zones, then you have to subtract the actual number

of time zones from 24 to calculate the actual number of hours

of jet lag that you will feel. For example, if you are flying

from Los Angeles to Hong Kong, you will pass through 16 time

zones, so you will experience 24 - 16 = 8 hours of jet lag—the

same as if you had flown through 8 time zones from, say,

London, England to Los Angeles.

For flights that cross the International Date Line, the calculation

is the same, but you do not have to take the date change into

account. |

|

|

Industrial

civilization, with innovations such as night

shiftwork, variable shiftwork, and intercontinental

air travel, has subjected the human brain to conditions that evolution never

foresaw.

For instance, when a businesswoman arrives in New York on a flight from Paris,

her endogenous

circadian rhythms are still synchronized with the time

of day in the French capital, but the ambient light signals

that her brain is receiving match the time of day in the

Big Apple, which is 6 hours earlier. Thus her need for

sleep is out of phase with the local time at her destination.

The uncomfortable symptoms known as jet lag generally start to appear when the

departure and arrival points for a flight are three or more time zones apart.

The most obvious of these symptoms is sleepiness in

the daytime and wakefulness in the middle of the night. But other symptoms may

include fatigue, loss of appetite, indigestion, headaches, nausea, irritability,

and a bad mood.

Over 75% of air travellers whose flights cross several time zones

report problems in sleeping the first night afterward. But after

three nights, this figure is down to 30%. It takes just about one

day to recover for every time zone that you travel through, but

this figure varies widely from one person to the next. People who

have a very regular routine when they are at home are more sensitive

to jet lag than people who lead less structured lives.

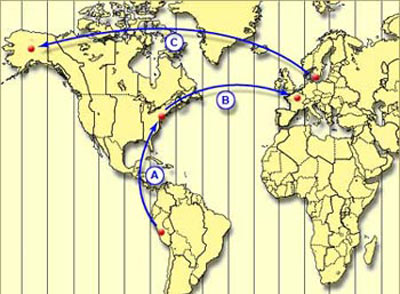

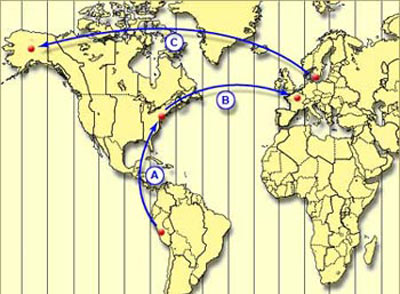

People do not experience jet lag when they fly from north to south or south to

north, even on long-haul flights such as from Lima, Peru to New York (flight

A in the diagram below). Because these people are staying

in the same time zone, their biological clocks are not thrown off, and all

they have to deal with is the fatigue due to the long period of immobility, which

is rapidly overcome.

On this map, flight B, from New

York to Paris, passes through 6 time zones and will cause its

passengers

moderate jet lag that takes them two to three days

to overcome. Flight C, from Copenhagen to Alaska,

passes through

11 time zones, and even though it is westbound rather than eastbound

(see below), will cause

very heavy jet lag that will take a good

week to dissipate.

Westbound long-haul flights are often said to cause less jet lag

than eastbound ones passing through the same number of time zones.

Many explanations have been offered to support this assertion.

One, which applies only to eastbound flights departing in the evening,

is that passengers on such flights may get only a few hours of

darkness in which to sleep before seeing the next sunrise.

Another explanation is that because

the human biological clock’s

endogenous cycle is naturally

slightly more than 24 hours long, and because westbound flights

through more than one time zone lengthen the passengers’ days,

such flights are easier for the body to recover from than eastbound

ones. But this hypothesis would seem to contradicted by experiments

in which westbound and eastbound time lags were simulated for animals

whose endogenous cycle was almost exactly 24 hours, and these animals

too experienced fewer physiological disturbances in the westbound

case.

In short, when it comes to jet lag, so many variables seem to

be involved and there seems to be so much variability among individuals

that it is impossible to state categorically which direction of

travel is more difficult.

The usual advice for reducing the effects of jet lag is as follows.

|

- Start to adjust your body to your

destination time zone in advance. If you will be flying

east, go to bed earlier and get up earlier. If you will

be flying west, go to bed later and get up later. The extra

time you spend awake in the morning in one case and in

the evening in the other will be more effective if you

spend it in a brightly lit environment.

- As soon as your flight takes off,

set your watch to the time at your destination.

- Once you arrive at your destination,

expose yourself to sunlight to help your biological clock

reset itself more quickly.

- During the days following your arrival,

be physically active and eat a balanced diet.

- And perhaps most important, make sure

you are well rested before your flight.

|

This advice is based on today’s scientific understanding

that jet lag consists of a desynchronization between our central

biological clock and our multiple

peripheral biological clocks.

There is much controversy

about whether melatonin can

be an effective treatment for the symptoms of jet lag. In

some studies, people have reported positive effects when

they took a dose of 0.5 mg to 5 mg of melatonin at bedtime,

local time, for the first few days after they arrived at

their destination. But other studies have found that melatonin

had none of the desired effects, nor any undesirable side

effects, at least in the short term.

In some countries, such as the United States, melatonin is

freely sold as a food supplement and represents a gigantic

market, worth $US 200 to 300 million per year. These supplements

may help to regulate sleep and are therefore widely used by insomniacs.

|

|

|