|

|

| People who consume alcohol

to the point of acute intoxication can experience “blackout” episodes:

periods in which they engage in conversations and perform tasks,

but of which they have no memory once they have sobered up.

Contrary to what was previously believed, their problem is

not in retrieving the memories, but rather in having failed

to store them in the first place. Sedatives such as barbiturates

and benzodiazepines can

also produce this kind of amnesia. |

|

|

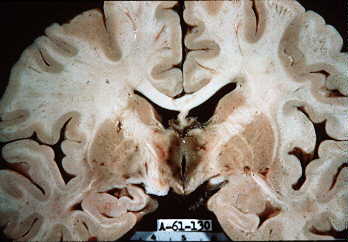

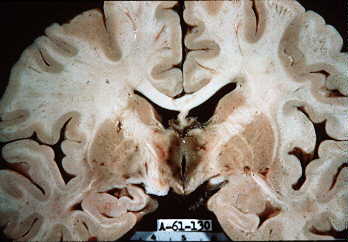

| LESIONS THAT CAUSE

AMNESIA |

|

The various

types of memory involve various structures in the brain,

and their destruction causes differing amnesic syndromes.

The best known of these is the global

amnesic syndrome experienced by patient

H.M., which was characterized by severe

anterograde amnesia and more moderate retrograde amnesia.

This syndrome results from bilateral lesions of the medial portion

of the temporal lobe, and more specifically, of the hippocampus

and its neighbouring structures (the parahippocampal, entorhinal,

and perirhinal cortexes). These lesions can be due to surgical

ablation, as in the case of H.M., or to other causes such as

tumours, ischemic episodes, head traumas, and various forms of

encephalitis.

Another well-known form of amnesia is Korsakoff’s

syndrome, encountered for the first time in chronic

alcoholics. Korsakoff’s syndrome is similar to global

amnesic syndrome, except that people with Korsakoff’s

are more prone to confabulation to cover up gaps in their memories

of their own past. Korsakoff’s syndrome is also known

as diencephalic amnesia, because the vitamin B1 deficiency

that results from alcoholism causes bilateral damage to the

mammillary bodies of the hypothalamus. Similar symptoms are

also produced by damage to the dorsomedial thalamic nuclei,

the mammillothalamic tract, and the upper portion of the brainstem.

Once again, other etiologies, such as strokes and tumours,

can affect the same structures and produce the same results.

Brain affected by Wernicke-Korsakoff

syndrome.

Note the pigmentation of the grey matter around the third ventricle.

Source: University of Texas (Houston)

There is also an amnesia of the frontal

lobe due to damage at this site. People with this disorder

do not suffer from global amnesia, but do show a memory deficit

in tasks involving temporal planning of sequences of events.

These people also have problems with the sources of newly acquired

knowledge and have deficient meta-memory (they cannot make judgments

about their memory’s contents).

Other types of damage to the cortex can cause

forms of amnesia that are sometimes highly specific. For

example, if the part of the cortex that perceives colours is damaged,

people can lose their knowledge of colour. And since the memory

of colours is reconstructed at this same location, this memory

disappears as well.

A specific injury to the amygdala can

prevent people from recording memories of traumatic events. In

normal people, such memories are formed when particularly stressful

conditions make certain details of a scene practically unforgettable.

Other localized cortical lesions can prevent

people from accessing certain items in their semantic memory and

thus cause all sorts of specialized aphasias.

Lastly, certain transitory global amnesias can

be triggered suddenly, causing people to completely lose their

memory for a few hours. Though these transitory amnesic episodes

are frightening, they are brief and do not cause any permanent

damage to the brain. They seem to be due to a temporary vascular

insufficiency in the brain tissue. |

|