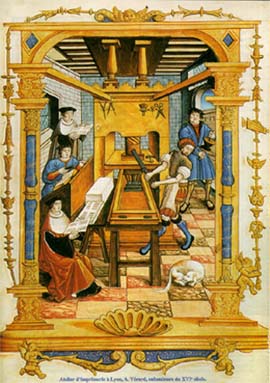

Until the

middle of the 15th century, monks working as scribes copied

manuscripts by hand using various writing techniques. But

around 1450, Gutenberg perfected certain methods that led

to the printing revolution. It was a revolution because

suddenly, large numbers of copies of written works could

be produced relatively easily.

By making books inexpensive, the

printing press allowed the dissemination of all kinds of

ideas and made a knowledge-based society possible. Books

spread knowledge not only of the experimental sciences,

but also of the humanistic ideas of Rabelais, Montaigne

and many other great authors. Thus, the printing press

opened the way to the publication of encyclopedias and

the Age of Enlightenment.

Printing Shop in Lyon. A. Vénard,

book illumination, 16th century.

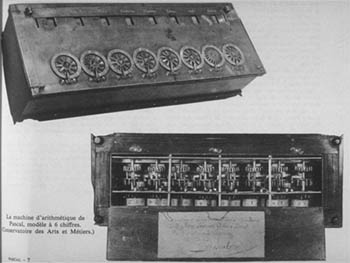

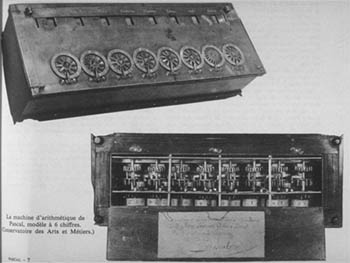

Pascal’s calculating machine

(1659), six-digit model: the ancestor of the modern computer.

Source: Conservatoire des Arts et

Métiers. |

|

Like the

invention of the printing press several centuries ago, the

advent of the computer is revolutionizing the human

ability to store information, images, and language. Today,

magnetic and optical technologies allow information to be

stored at speeds and densities that were unimaginable just

a few years ago.

In computer systems, there are two main types of peripheral

devices on which information is stored: magnetic storage

devices and optical storage devices. On magnetic hard drives

and diskettes, information is stored through the orientation

of tiny magnetic particles. On traditional optical disks

(CDs), information is stored in microgrooves of varying

lengths etched into the disk, and read back by means of

laser beams.

Writing, printing, and computers are tools that let us associate

meanings with representations. And this human societies externalization

of our representations and our memories could almost

be described as the chief characteristic of human

societies.

With the invention

of writing, society’s memory no longer depended

on individuals’ memories, but instead could

be externalized in a tangible, portable, reproducible

form. Past events could now be relived at will, even

if those who witnessed them were no longer alive.

But writing also fostered

the development of thought, by providing new intellectual

tools such as lists, tables, formulas, computation

algorithms, and so on. The availability of such

reliable, extensible forms of external working

memory also enabled people to deploy their thoughts

beyond the limits of their individual, internal working

memories. The result was the subsequent

invention of still more elaborate cognitive artifacts,

such as maps and calculating instruments, of which

today’s computers are the culmination.

The creation of computer networks and the Internet

represents a still newer form of external memory

that can classify and pre-process information for

us. This phenomenon is still too recent for its cognitive

and cultural effects on human beings to be discerned,

but we can already predict that these effects will

be substantial.

|

|