|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In addition to benzodiazepines, antidepressants,

and neuroleptics, certain antihistamines (such as hydroxyzine)

have sedative properties and are used to treat certain

relatively short-term forms of anxiety.

Some serotonergic

5-HT1A receptor agonists, such as buspirone, by activating

the serotonergic autoreceptors, reduce the secretion of serotonin,

thus producing an anxiolytic effect comparable to that of medications

which activate GABA receptors, such as benzodiazepines.

The fact that certain serotonin-reuptake-inhibiting antidepressants

(substances such as fluvoxamine, which increase the secretion

of serotonin) can be used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder

shows at least two things. First, the amount of a neurotransmitter

is too vague a criterion to account on its own for all of the

complex phenomena involved in anxiety disorders. Second, anxiety

and depression probably

involve some similar biological mechanisms. For example, we

know that people who have anxiety disorders in childhood are

at greater risk for developing depression later in life.

|

|

|

|

|

Tranquilizers should not be prescribed automatically whenever

anxiety symptoms are present, because these symptoms are

not considered pathological unless they become disabling

for the person experiencing them. At that point, they warrant

specific treatment, most often with benzodiazepines, which

can be prescribed temporarily without any significant negative

health effects. In such cases, benzodiazepines can generally

effectively reduce the anxiety that the person is experiencing,

but they cannot attack its underlying causes. |

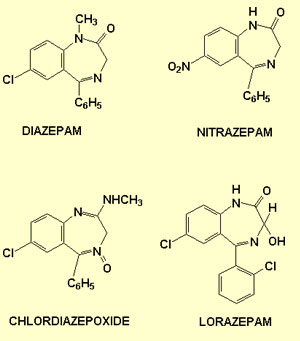

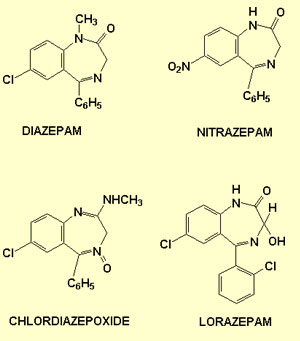

The term “benzodiazepine” refers

to the general class of chemicals to which these molecules belong.

Each member of this class has a generic name or is simply known

by its trade name. The following table lists some of the most common

benzodiazepines.

| Generic name (active ingredient) |

|

Marketed under the trade name(s): |

| |

|

|

| Diazepam |

|

Valium, Vivol, T-Quil, Valrelease |

| Lorazepam |

|

Ativan, Alzapam, Loraz |

| Alprazolam |

|

Xanax, Alprazolam Intensol |

| Chlordiazepoxide |

|

Librium, Novopoxide, Libritabs |

| Flurazepam |

|

Dalmane, Novoflupam, Somnol |

| Nitrazepam |

|

Mogadon |

| Triazolam |

|

Halcion |

| Temazepam |

|

Restoril |

| Oxazepam |

|

Serax |

Researchers have long known that benzodiazepines bind

to GABA-A

receptors, thus facilitating the opening of their chloride

channels and potentiating GABA's inhibitory effect. But now researchers

are increasingly finding that the

specific effects of each type of benzodiazepine seem to be

directly linked to the various types of GABA-A receptors to which

it can bind (GABA-A receptors are made up of sub-units designated

alpha, beta, and gamma, and the various types of GABA-A receptors

represent varying arrangements of these sub-units).

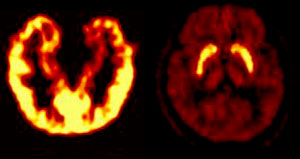

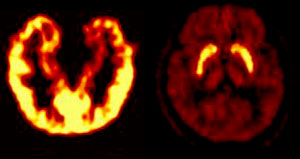

Left: distribution of benzodiazepine

receptors in the brain. Right: distribution of D2 dopaminergic

receptors

Source: CERMEP, Hôpital Neuro-Cardiologique de Lyon |

|

Research suggests that

different benzodiazepines may have differing affinities for

these various types of GABA-A receptors, which may in turn

explain why one benzodiazepine has more of an anxiolytic effect

while another has more of a sedative effect. Also, some studies

show a marked variation in the distribution of these various

kinds of benzodiazepine receptors within the brain. For example,

the type of benzodiazepine receptor that predominates in the

motor and sensory cortexes is not the same one that predominates

in the circuits

of the amygdala and the other structures of the limbic

system. |

These studies thus support the idea that

the distinctive effects of various benzodiazepines are associated

with the different types of receptors and their distribution in

the brain.

Some studies

seem to show that endocannabinoids—substances that

are analogous to the active ingredient in cannabis but that

are produced inside the human body—help to extinguish

painful memories through their inhibitory effect

on the internal

circuits of the amygdala.

In one study, for example, mice that had been genetically altered

so that they did not express the endocannabinoid receptor had

much more trouble in extinguishing a conditioned fear, even

though they did not display any other memory problems. (The

same result was also obtained when the endocannabinoid receptor

was blocked with an antagonist.)

While the mice were being exposed to the stimulus that led

to the extinction of the response, the researchers also found

high levels of endocannabinoids in the basolateral

nucleus of the amygdala, which is known to be involved

in the extinction of painful memories. This extinction seems

to involve the activation of NMDA

receptors by glutamatergic neurons. Endocannabinoid

receptors are known to have an inhibitory effect on the GABAergic

inhibitory neurons in the basolateral nucleus. Hence one

can see how inhibition of these inhibitory neurons by endocannabinoids

might lead to activation of the NMDA receptors and thus facilitate

extinction of the conditioned fear.

The psychotherapeutic treatment for many anxiety disorders

(including phobias)

is based on a process of extinction (placing the patient in

contact with the feared object in the safe setting of the therapist's

office). Hence, if a substance that increased the levels of

endocannabinoids at the right places in the patient's brain

could be administered during psychotherapy, it might facilitate

a cure. (This probably would not be the case if the patient

simply smoked a joint, flooding the entire brain with THC.)

Lastly, there are other molecules that also may help to extinguish

painful memories. Some of these molecules activate the NMDA

receptors in the amygdala, which are also involved in the

process of extinction.

|

|

|