|

|

|

|

|

Communicating in Words |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When these studies were published in the late 1990s and the

early 2000s, some mass media rushed out with reports that

the “language gene” had been discovered. In reality,

of course, a phenomenon such as language is far too complex

to reside on a single gene. To be more accurate, the media

should have talked about “a gene that might be involved

in language”, and even more precisely, as regards specific

language impairment, in the development of the brain

structures that underlie language.

The fact is that discovering a gene is only the first step

in understanding what role it plays. The subsequent steps,

which inevitably require identifying the structure

and function of the protein produced by this gene,

generally prove longer and more arduous.

It’s as if you were trying to understand how a car works

when all you had to go by was a diagram of one of its parts.

No matter how much evidence you had that this diagram did indeed

represent a car part, you would have no idea what the part

really looked like, or what it did, or what other parts interacted

with it, much less what the car as a whole did and looked like. |

|

|

| GENES THAT ARE ESSENTIAL FOR SPEECH |

|

The ability of human beings

to speak involves very fine motor control of the mouth and

the larynx (voice box), a kind of control that other primates

lack.

Research done by the American linguist Noam Chomsky in the

late 1950s and early 1960s highlighted the fact that human

language is universal and complex, yet children acquire it

rapidly with no explicit instructions. Chomsky’s findings

suggested that the human ability to speak might have genetic

origins.

Around the same time, other researchers pointed out that a

small number of children failed to learn to speak. They had

problems in producing and identifying the basic sounds of language

as well as in understanding grammar. This condition is called “specific

language impairment”,

and it includes all language disorders that cannot be attributed

to mental retardation, autism, deafness, or any other very

general causes.

Researchers also observed

that specific language impairment often occurred in more

than one member of the same family and was more likely to

be shared by identical twins than by fraternal ones. Scientists

therefore long suspected that this condition had a hereditary

component, but they did not know much about the genes that

were involved.

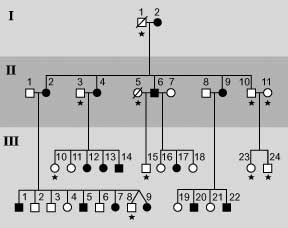

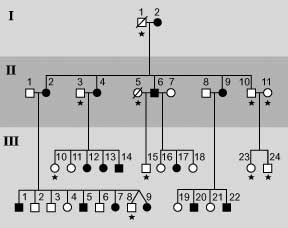

All this changed, however, after a study of a British family,

known as the KE family. In this family, out of 37 members

distributed across 4 generations, 15 suffered from some form

of specific language impairment. This high proportion of affected

individuals within the same family indicated, first of all,

that this disorder might be attributed to a single gene transmitted

by either parent. In addition, this gene seemed to be transmitted

by the standard dominant/recessive pattern and was not located

on a sex chromosome.

|

Genealogical tree of the KE

family. Black shapes represent persons with specific language

impairments. Circles represent females, and squares represent

males.

|

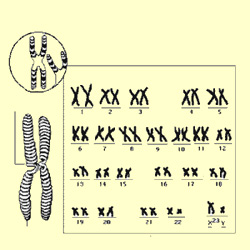

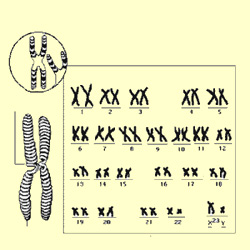

The 23 pairs of human chromosomes

at the time of mitosis

|

In 1998,

scientists established a relationship between specific language

impairment and a short segment of chromosome 7. Even this

short segment still contained 70 genes, so analyzing them

would be an arduous task. But then, as luck would have it,

researchers became aware of “CS”,

a young English boy who had specific language impairments

but was not a member of the KE family. Because CS had a

visible defect on chromosome 7, the researchers immediately

focused their efforts on this defective segment of DNA.

And as they expected, this gene, which they named FOXP2,

turned out to be directly correlated with specific language

impairment.

As in the identification of any other gene, the next step,

of course, was to find out what

type of protein this gene produced. |

|

|